Working out of Athens, Vicky Tsalamata brings a firm, unsentimental eye to her art. She’s not interested in trends or ornament. As a Professor Emeritus in Printmaking from the Athens School of Fine Arts, she knows her tools inside out—archival prints, layered mixed media, and the soft grain of Hahnemühle cotton paper. But technique is only part of the story. Her real work lies in peeling back appearances. Drawing on references like Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine and echoes of Dante’s Divine Comedy, she holds a mirror to the messy contradictions of human life. Her art walks through the past with one foot in the present, pointing not at what flatters us, but what undermines us—what systems we’re caught in, what illusions we accept, and how easily we trade meaning for survival. Her pieces don’t offer shelter. They ask for honesty.

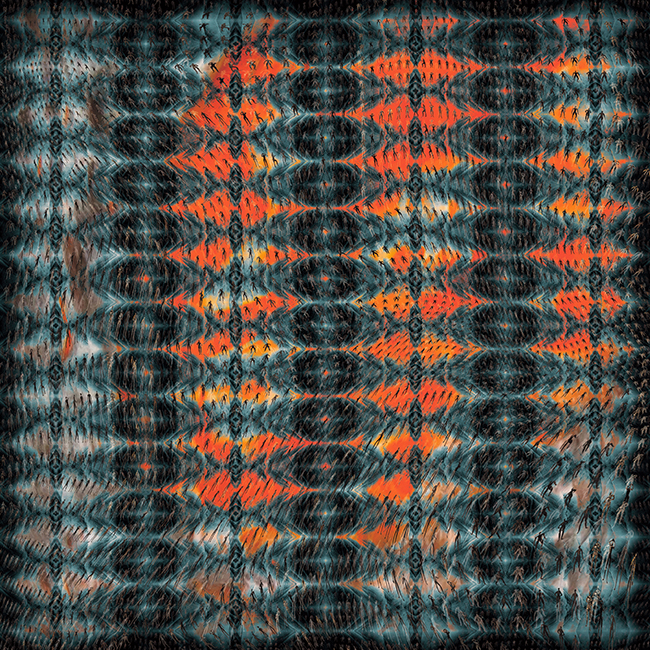

In La Comédie Humaine, Give Me Your Hand (2022), the title suggests connection, but the image does something else. There’s tension in the gesture. It could be welcome or warning—maybe both. The piece is careful, composed, and emotionally dry. Her mixed media process builds the image slowly, layering depth and contrast while keeping everything slightly out of reach. The hand, if it’s even meant to comfort, is lost in the noise of the surrounding emptiness. The space between the elements reads like emotional distance. Isolation hangs in the composition. It doesn’t shout, but it leaves a chill. The work points to how our structures—social, familial, institutional—so often fall short of bringing us closer. We may reach out, but the ground underneath keeps shifting.

One year later, La Comédie Humaine, Farewell (2023) closes the door that Give Me Your Hand left ajar. This isn’t about personal grief. It’s about a collective letdown—a parting from ideals that no longer hold. The title, like the work, is spare and loaded. There’s a sense of systems unraveling, not with chaos, but with a kind of mechanical inevitability. The atmosphere is tight. Clean lines, contained form, and deliberate control point to a world that appears orderly even as it corrodes. The nod to Dante isn’t theatrical. It’s structural. This is purgatory dressed as progress. Tsalamata uses simplicity to speak volumes. The image doesn’t aim to resolve anything. It just lays the pieces in front of us and waits. It’s the kind of clarity that comes after illusions fall away.

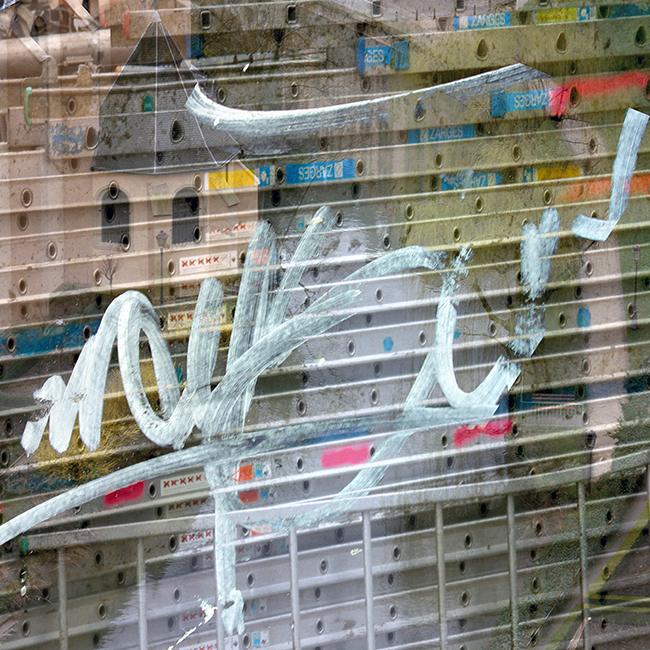

Tsalamata’s Cityscapes: Utopian Cities takes a different road but keeps asking the same questions. Here, she blends travel photography with fragments of intaglio print work. The results are imagined urban environments—unreal, but stitched from real-world materials. These cities don’t sell a perfect future. They raise the question: what would coexistence look like if we were brave enough to redraw the map? The layers in the work speak to history and aspiration, collapse and possibility. Her expanded printmaking techniques allow her to treat the photograph as something that can be reshaped, as though the past isn’t fixed and the future isn’t promised. These images carry a quiet tension. They don’t preach utopia. They simply point to what’s possible, and what’s already broken.

Across these series, what stays constant is Tsalamata’s commitment to discomfort. She doesn’t give us easy narratives. Give Me Your Hand holds back comfort. Farewell doesn’t close with hope. Even in Utopian Cities, there’s hesitation in the promise. Tsalamata keeps things bare and unsentimental. Her tone is cool, restrained, and exacting. Every decision feels earned. Every surface hides something more. She doesn’t push interpretation; she leaves room for us to sit with the weight of what we see.

What gives the work its staying power isn’t just subject or method—it’s her belief in longevity. Archival paper and layered printing aren’t just about quality. They’re about time. These are works made to be revisited, not consumed. You don’t “get” them in a glance. Like a dense book or a half-remembered dream, they ask for patience. And with time, they offer more—not loud revelations, but quiet, necessary truths.

Tsalamata’s art doesn’t compete for attention. It waits, holds steady, and lets the viewer catch up. It offers something rare: the chance to stop, think, and really see.