In a quiet corner of Germantown, Philadelphia, Oronde Kairi creates art that hums with life. His paintings are full of movement and feeling, grounded in the rhythms of the city and the culture that shaped him. His subjects often come from music, sports, and urban history, but the way he approaches them makes them feel personal—less like icons, more like familiar voices in the room.

Kairi’s visual language is bold—bright color, strong lines, and expressive composition—but what makes his work land is its sense of place and memory. He captures the everyday and makes it vivid: a streetlight, a denim jacket, a quiet moment before the music starts. His art doesn’t just reflect Black culture—it participates in it. It remembers, honors, and celebrates, all while staying grounded in real life. It’s work that speaks clearly and directly, with heart.

Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1

“Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1” is more than a portrait—it’s a moment frozen in sound. The painting shows Gaye during the recording of Let’s Get It On, captured in a way that feels both intimate and timeless. Kairi gives us Marvin seated, eyes closed, hands joined together, immersed in his craft. The red skull cap and denim outfit match the album era. The details—like the old-school tape recorder and wood-paneled studio—build the world around him.

This is a quiet painting, not in energy but in spirit. Kairi isn’t chasing glamor. He’s honoring a creative process. The painting feels like a prayer in motion, with Marvin deep in concentration, mid-verse. There’s no spotlight—just a man and his music. The brushwork and tones give it warmth, and the setting wraps around the figure like a memory. The result is emotional. It brings us close to an artist in his zone.

Sweet Prince of the Ghetto

With “Sweet Prince of the Ghetto,” Kairi taps into television history and reclaims it. JJ from Good Times—played by Jimmy Walker—is reimagined not just as comic relief, but as a working artist, seated in the Evans family’s living room, painting The Sugar Shack. This is a layered tribute: to the show, to Black creativity, and to Ernie Barnes, whose influence is felt in the stretched proportions and musical flow of the scene.

JJ is shown as focused and thoughtful, surrounded by the textures of the 1970s—furniture, records, color tones. He wears his signature denim, but he’s not joking or posing. He’s building something. Kairi turns a familiar face into a cultural builder. The vibe is both nostalgic and alive.

This piece looks back with love but also insists on a deeper reading of the past. It’s about celebrating Black culture as something complex and ongoing—not a moment, but a movement.

Midnight Melody

“Midnight Melody” shifts tone. It’s spare, moody, and full of space. A lone saxophonist stands under a streetlamp in a narrow alley, his shadow stretching long and quiet. We don’t see the music, but we feel it. Kairi leaves enough unsaid for the viewer to fill in the blanks. The atmosphere does the talking.

Everything here feels suspended: time, sound, even the figure himself. The painting suggests solitude, but not sadness. It leans into the late-night feel of jazz—the kind played in empty rooms, echoing down streets, disappearing into the night. The composition invites stillness. You don’t just look at it. You wait with it.

Where some of Kairi’s other works are loud with color and motion, this one is hushed. But it still sings. It’s about what music carries when no one’s listening, and what it leaves behind when it fades.

Kairi’s paintings are about presence—being present with memory, sound, and people. He brings everyday heroes into view and gives the past a voice that still resonates. His art isn’t meant to be decoded. It’s meant to be felt. And in that way, it does exactly what it’s supposed to: it speaks.

In a quiet corner of Germantown, Philadelphia, Oronde Johnson—who signs his work as Oronde Kairi—creates art that hums with life. His paintings are full of movement and feeling, grounded in the rhythms of the city and the culture that shaped him. His subjects often come from music, sports, and urban history, but the way he approaches them makes them feel personal—less like icons, more like familiar voices in the room.

Johnson’s visual language is bold—bright color, strong lines, and expressive composition—but what makes his work land is its sense of place and memory. He captures the everyday and makes it vivid: a streetlight, a denim jacket, a quiet moment before the music starts. His art doesn’t just reflect Black culture—it participates in it. It remembers, honors, and celebrates, all while staying grounded in real life. It’s work that speaks clearly and directly, with heart.

Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1

“Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1” is more than a portrait—it’s a moment frozen in sound. The painting shows Gaye during the recording of Let’s Get It On, captured in a way that feels both intimate and timeless. Johnson gives us Marvin seated, eyes closed, hands joined together, immersed in his craft. The red skull cap and denim outfit match the album era. The details—like the old-school tape recorder and wood-paneled studio—build the world around him.

This is a quiet painting, not in energy but in spirit. Johnson isn’t chasing glamor. He’s honoring a creative process. The painting feels like a prayer in motion, with Marvin deep in concentration, mid-verse. There’s no audience, no spotlight—just a man and his music. The brushwork and tones give it warmth, and the setting wraps around the figure like a memory. The result is emotional. It brings us close to an artist in his zone.

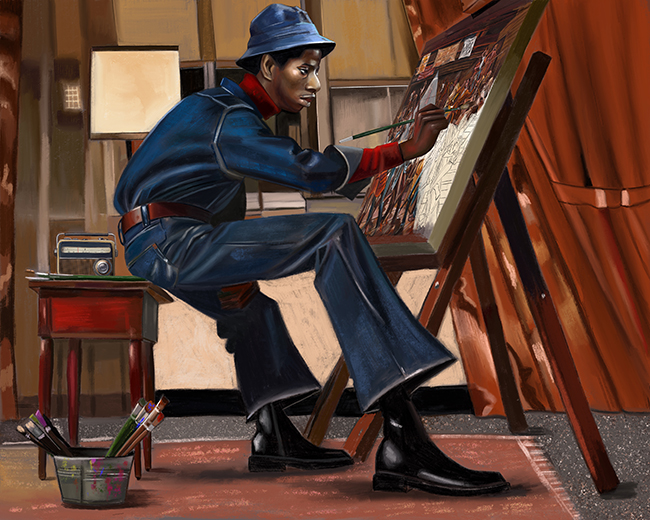

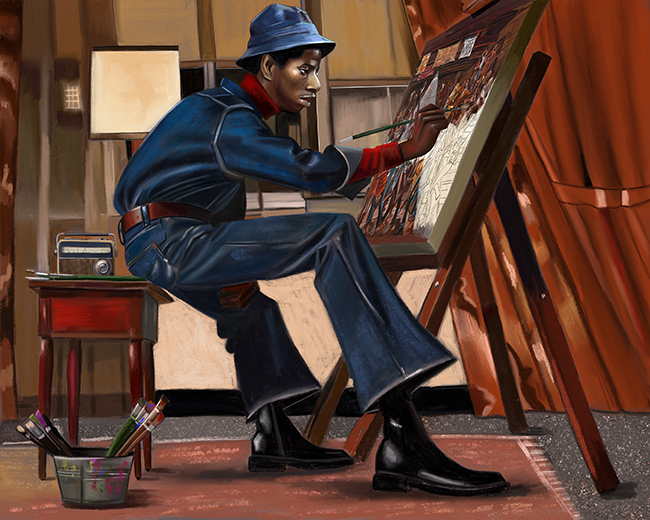

Sweet Prince of the Ghetto

With “Sweet Prince of the Ghetto,” Johnson taps into television history and reclaims it. JJ from Good Times—played by Jimmy Walker—is reimagined not just as comic relief, but as a working artist, seated in the Evans family’s living room, painting The Sugar Shack. This is a layered tribute: to the show, to Black creativity, and to Ernie Barnes, whose influence is felt in the stretched proportions and musical flow of the scene.

JJ is shown as focused and thoughtful, surrounded by the textures of the 1970s—furniture, records, color tones. He wears his signature denim, but he’s not joking or posing. He’s building something. Johnson turns a familiar face into a cultural builder. The vibe is both nostalgic and alive.

This piece looks back with love but also insists on a deeper reading of the past. It’s about celebrating Black culture as something complex and ongoing—not a moment, but a movement.

Midnight Melody

“Midnight Melody” shifts tone. It’s spare, moody, and full of space. A lone saxophonist stands under a streetlamp in a narrow alley, his shadow stretching long and quiet. We don’t see the music, but we feel it. Johnson leaves enough unsaid for the viewer to fill in the blanks. The atmosphere does the talking.

Everything here feels suspended: time, sound, even the figure himself. The painting suggests solitude, but not sadness. It leans into the late-night feel of jazz—the kind played in empty rooms, echoing down streets, disappearing into the night. The composition invites stillness. You don’t just look at it. You wait with it.

Where some of Johnson’s other works are loud with color and motion, this one is hushed. But it still sings. It’s about what music carries when no one’s listening, and what it leaves behind when it fades.

Johnson’s paintings are about presence—being present with memory, sound, and people. He brings everyday heroes into view, and gives the past a voice that still resonates. His art isn’t meant to be decoded. It’s meant to be felt. And in that way, it does exactly what it’s supposed to: it speaks.