Sylvia Nagy works in the space where hand-built skill meets bigger frameworks—where a ceramic form can carry private feeling while still echoing ideas about technology, process, and a world in motion. Her background moves between industrial design and fine art, and you can feel that dual training in how she treats material: with respect for structure, but also room for intuition. She studied at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest, completing an MFA in Silicet Industrial Technology and Art, a program that honed her understanding of fabrication and how concepts translate into physical reality. Over time, that technical focus widened into ceramics as a fuller language—especially during her connection to Parsons School of Design in New York. There, she taught and also created a course centered on plaster mold model-making, using a traditional method as a platform for contemporary ideas. What emerges is a practice that stays rooted in the studio—tactile, direct, hands-on—while constantly pointing outward, linking mediums, places, and moments as parts of one ongoing conversation.

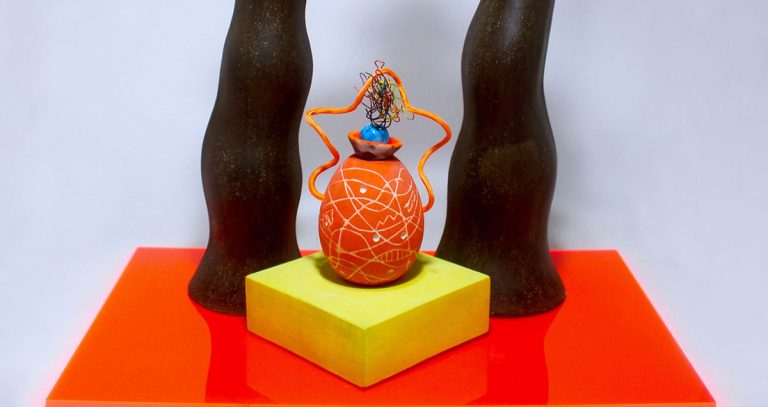

Square in Space

At first glance, Square in Space sounds almost spare—a clean shape, a clear boundary. But Nagy treats that basic geometry as an entry point into complexity: how parts relate, how patterns shift, and how one artwork can hold many kinds of knowledge at once. She often returns to a core belief: everything connects. For her, that’s not a poetic line—it’s a practical way of working. Painting, ceramic design, sculpture, dance, music, science, technology, nutrition: these interests don’t sit neatly side by side. They blend, overlap, and feed each other. Even glaze chemistry becomes more than technique—it mirrors her broader attraction to mixing, transformation, and the chain reaction of one element changing another.

That layered mindset begins long before ceramics takes center stage. Nagy’s early training was rooted in mural traditions at the Budapest School of Fine and Applied Arts, where she studied sgraffito, fresco, and mosaic. These are demanding forms: they require planning, patience, and a commitment to longevity—images made to endure beyond the moment they’re created. In the same environment, she encountered sculpture assignments and ceramic courses, and the range of possibilities started to open. Painting remained important, but she felt drawn toward clay—toward depth, mass, surface, and the physical presence an object can hold.

Sound is part of her process, too. She recalls studying with music playing loudly, even when others didn’t understand how that could help. For Nagy, it wasn’t background noise—it was a kind of momentum. She still works that way, moving between tasks while music keeps time in the room. She doesn’t rely on other people to validate the method. She follows it because it matches how she thinks and how she makes. In Square in Space, that approach becomes almost structural: the work allows complexity without apology. It accepts tension—focus with noise, discipline with freedom, private concentration with the pressure of the outside world.

When Nagy shifted from mural painting to ceramics at Moholy-Nagy University, she didn’t abandon scale—she brought it with her. She studied industrial ceramic technology while also gaining experience with large sculptural work, and the pairing matters. Industrial thinking teaches repeatable systems, engineering logic, and how materials behave through heat, pressure, and time. Sculptural thinking invites risk, instinct, and the ability to let form communicate without explanation. Nagy keeps both modes active, letting precision and expression push against each other until something new appears.

She describes an intense period of production: completing a multi-piece mural installation in four weeks by working day and night. She calls it a personal record—an extreme stretch of endurance and drive. But the part that lingers isn’t only the speed. It’s what followed. Recognition and results didn’t arrive immediately. The response came years later, after she had stopped waiting for it. That delay—between effort and outcome—shapes how she thinks about time in art. Sometimes you can’t fully understand what you’ve made while you’re still inside it. Sometimes the meaning only becomes visible after distance, after life has shifted, after you’ve moved on.

This is where Square in Space starts to feel like a model for transition itself. Nagy connects her work to the way societies cycle through change—periods of conflict, rethinking, repair, and reinvention. She points to the 1960s phrase “Love, not war” as proof that history repeats its pressures and its hopes. In every era, there are missing pieces—“empty squares” in the larger grid: gaps in understanding, empathy, and shared information. Her work doesn’t pretend to complete the board. Instead, it notices the missing parts and traces relationships—how one square touches the next, how patterns form, how a single shift can alter the whole field.

Her lived environments reinforce that sense of movement. She speaks about settling in Romhild Castle in Germany, a place marked by history and scale. A castle suggests permanence, but it also proves how unstable permanence really is—structures remain while meanings change, again and again, over generations. In that setting, Nagy’s movement from murals to sculpture to installation feels inevitable. The work becomes spatial thinking: not just objects on view, but environments and experiences—forms that shape how you move, pause, and connect ideas in real time.

At the center of Nagy’s practice is a quiet, steady reason for making: art helps her find calm. She’s clear that she doesn’t claim full knowledge of every political or historical force behind global shifts. But she doesn’t need total certainty to create. She needs responsiveness—the ability to build a form that holds curiosity, feeling, and repair. Square in Spacebecomes a container for that kind of thinking: structured, but open; disciplined, but breathable; grounded in material, yet always reaching toward connection.

In Nagy’s hands, connection isn’t a decorative theme—it’s the engine. And the square is never just a square. It’s a unit within a larger field: influencing, responding, and staying in motion.