Working from Athens, Greece, Vicky Tsalamata builds prints that look in two directions at once. They draw from literature, myth, and moral narrative, yet they stay fixed on the frictions of contemporary life—how people relate, what power protects, and what gets traded away in the process. Her ongoing dialogue with Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine isn’t a reenactment or a nod for its own sake. It’s a tool. Balzac’s wide social lens becomes Tsalamata’s way of reading the present: patterns of behavior, public performance, quiet cruelty, and the everyday negotiations that keep systems running.

The key is her voice. There’s intelligence and humor, but it’s edged, not charming. Her sarcasm doesn’t hover above the work as a caption—it’s woven into the imagery and the structure, shaping how the work lands. Tsalamata is interested in collisions: a world that never stops talking yet feels emotionally sparse; “progress” that can sit beside moral drift; speed that gets mistaken for purpose. Her prints slow the viewer down and ask a blunt question: when worth is measured through status, productivity, and visibility, where does that leave anyone who doesn’t fit the scoreboard?

That gap—between the story we’re sold and the reality we inhabit—threads through her major works. In La Comédie Humaine, she charts society like a terrain of forces. In Impulse, she tracks time as pressure, motion, and loss. Across both, the subject remains consistent: human behavior under strain. The work can be unsparing, but it doesn’t collapse into doom. Beneath the critique is an insistence that human contact is still essential—that communication isn’t optional, and that love and friendship aren’t soft ideals but real supports. The message isn’t “nothing matters.” It’s closer to: what matters is being threatened, so treat it accordingly.

“La Comédie Humaine”

Tsalamata’s La Comédie Humaine opens with a title that carries weight. Balzac’s project was a sweeping portrait of society—ambition and compromise braided together, private motives hidden inside public roles. Tsalamata extends that panoramic thinking and draws in Dante’s Divine Comedy, a work built around consequence and moral accounting. The pairing is telling: the crowd on one side, judgment on the other.

Yet Tsalamata’s stance is unmistakably current. Her work doesn’t deliver tidy moral outcomes. It feels more like a document made from within the machinery rather than a lecture delivered from above it. The irony is aimed at how the world can keep shifting socially and economically while repeating the same patterns of domination. In her framing, the “grand scheme” isn’t a comforting perspective; it’s a weight that presses down. It’s the sensation of being reduced—moved, managed, dismissed—treated like a unit rather than a life.

She describes the work as a universal map, but it isn’t a map for guidance. It’s a map that shows what’s acting on us: economic churn, moral shifts, social theater, and the hard corruption inside political and social systems. In that reality, the weak are crushed and the corrupt gain protection, confidence, and momentum. What makes her statement sharp is its refusal to pretend this is a new crisis. She points to past and present, suggesting recurrence: different eras, similar results. The costumes change. The language changes. The tempo speeds up. The core pattern keeps returning.

Then the work turns, and that turn matters. Tsalamata points to the hunger underneath the noise: the need for communication between people. She calls out love and friendship as forces that should take a central role. This is not sentimentality; it’s a structural claim. If systems train people to detach, to self-protect, to treat others as disposable, then care becomes a counterweight. In that sense, La Comédie Humaine isn’t only critique. It is also a reminder of what gets erased when society becomes a contest: attention, loyalty, mutual recognition, the basic act of showing up for one another.

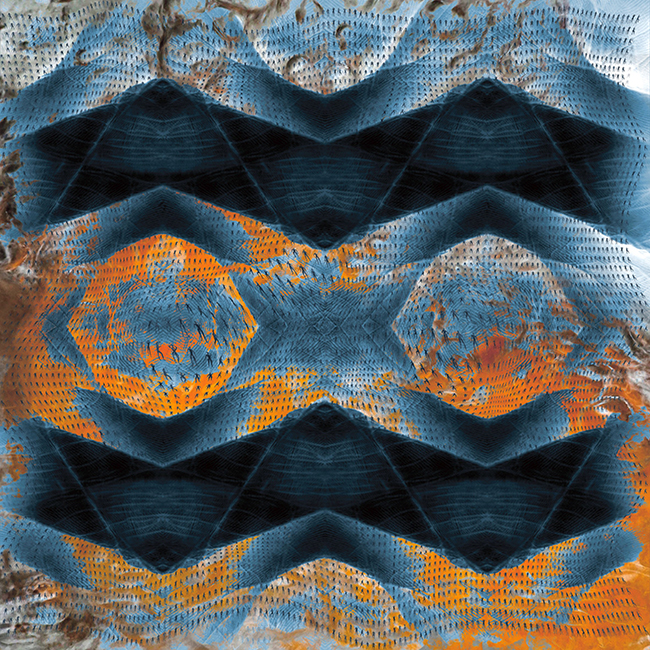

Her process reinforces the work’s constructed complexity. La Comédie Humaine uses intaglio and mixed media combined techniques, built from seventeen iron matrices worked through intaglio methods. Seventeen matrices signals accumulation and layering—an engineered build rather than a single gesture. Iron carries its own emotional register: industrial, durable, severe. It suits a project about pressure and power. The press becomes more than a tool—it becomes part of the meaning, turning force into image.

A related work, La Comédie Humaine B’, was selected for the Main Exhibition of the Guanlan International Print Biennial Nomination Exhibition 2025 at the Guanlan Printmaking Museum, on view from December 20, 2025 through April 2026. That placement situates her work inside a global conversation about contemporary printmaking, where technique and ethics sit side by side.

“Impulse”

Where La Comédie Humaine spreads outward across society, Impulse tightens into time. Produced in 2025 as an edition of 45 for Patanegra Editions in Spain (52 x 38 cm), the work treats time as lived velocity—an unstoppable current. Tsalamata frames the concept through “kinetic momentum,” the drive of modern life that keeps people moving even when they aren’t sure what they’re moving toward.

Her focus here is both ordinary and unsettling: how speed becomes normal, and how people adapt until detachment feels like the default setting. She points to the ways we ignore time’s rhythm even while it dictates everything—deadlines, routines, constant alerts, constant pressure. In her description, people become spectators to their own lives, watching real life run parallel to them. The image is quiet, and that’s why it sticks. No dramatic collapse is necessary. Drift is enough.

Impulse connects to Heraclitus’ “Everything flows,” not as decoration, but as a reminder that time doesn’t bargain. You can’t pause the river. You can only decide whether you notice it. The work is part of Tsalamata’s broader project Awareness, presented as an installation at the Krakow International Triennial in 2024, and it continues into an international collaboration slated for 2026: the XII Graphic Arts Folder project, “XII Contemporary International Graphic Amalgam, 20 American Graphic and 20 European Graphic,” bringing together invited printmakers across regions.

In that larger context, Impulse becomes both individual and shared—one artist’s statement that also fits inside a collective framework of editions, folders, and exchange. Printmaking itself is time-based: stages, sequences, returns, patience. Tsalamata uses that discipline to speak back to the era’s impatience, asking what it might mean to reclaim attention before the day disappears.

Conclusion

Tsalamata’s work doesn’t cushion its observations. It stays precise, ironic, and clear-eyed—tracking how power operates, how speed rewires living, and how loneliness can hide inside constant connection. But under the critique is a steady human insistence: slow down enough to see each other, speak honestly, and treat love and friendship as real supports. In her hands, printmaking becomes a record of pressure—and a prompt to choose attention as a daily act.