One of the leading artists of her generation, Faith Ringgold is known for her involvement in the American civil rights struggle and the power of feminism as well as her captivatingly illustrated and narrated children’s books. Passed away at home.

Ringgold is known for the visceral quality of her political paintings of the early 1960s—her The American People Series #20: Death (1967) is a landmark in 20th-century American art—because of the haunting power of her textile narratives.

Writer and cultural critic Rebecca Carroll took to Instagram today to describe Ringgold as “one of the greatest artists … to interweave time and beauty, storytelling and ancestry through a variety of mediums.” Elegance comes together, especially in her beautiful, surprisingly vivid quilt pieces.”

Faith Jones was born in 1930 in Harlem, New York City, to Andrew Louis Jones, a sanitation truck driver, and Willi (Posey) Jones. ) is a seamstress and fashion designer. Writers, musicians, and artists such as Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, Thurgood Marshall, and Billie Holiday all lived nearby and knew her family.

She suffered from asthma as a child and was home-schooled until the age of eight under the guidance of a doctor. Her parents encouraged her to paint from an early age. She attended City College of New York, earning a bachelor’s degree in art and education in 1955 and an MFA in 1959. to her art.

“The American People” Series

Ringgold broadened her artistic training by traveling in Europe in the early 1960s and 1970s and in Africa in the late 1970s.An important stage in Ringgold’s career was american people The series was produced between 1963 and 1967, a time when she was actively involved in the civil rights movement. The piece, which incorporates African textile patterns, marks her break from reliance on European masters, having been part of her classical training at City College.

“I’m fascinated by art’s ability to document an artist’s time, place and cultural identity,” she told The Art Newspaper 2019. “As an African American female artist, how do I document what’s going on around me?”

she includes The American People Series #20: DeathIn 1967, she held her first solo exhibition at Spectrum Gallery in New York. Guernica (1937)—which Ringgold studied during a long-term loan to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from 1939 to 1981—was released in 2016, nearly half a century after Ringgold’s involvement in the demonstrations. MoMA Acquisitions fights against the exclusion of black and female artists from the institution and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

“I just want the riots and hatred and violence to end,” Ringgold said The Art Newspaper In an interview in 2019, it was mentioned die. “I went through a period in the United States where violence would break out on its own — maybe in a movie theater, maybe on the street — and you didn’t know where it was coming from. All you knew was that you were going to grab your kids. and tried to get out of there.

“A Kick in the Face of a Painting About Racial Violence”: The Works of Faith Ringgold The American People Series #20: Death (right) Hanging with works by Pablo Picasso ladies of avignon In the room after the 2019 re-exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art Photo: DPA/PA Images. Artwork: Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London; © 2024 Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.Courtesy of ACA Gallery

Jillian Steinhauer, looking back at Ann Temkin’s 2019 rearrangement of the Museum of Modern Art The Art Newspaperwrote: “Written in New York Timessaid Holland Cote Faith Ringgold location The American People Series #20: Death (1967), a painting about racial violence located near Picasso’s landmark ladies of avignon (1907) “A stroke of curatorial genius”; I agree.

Ben Luke looks back at the best exhibitions of 2023 for The Art Newspaperselected “Beyond” Faith Ringgold: Black is Beautifula slightly smaller version of the retrospective at the Picasso Museum in Paris, Faith Ringgold: The American Peopleto be held at the New Museum in New York in 2022. The American People Series #20: Death In Paris,” Luke writes, “there Picasso painted the work that inspired him, Guernica (1937), summed up the emotional power of the exhibition.

public activist

Ringgold was a prominent black and feminist activist in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1970 she co-founded with Lucy Lippard, Poppy Johnson, Brenda Miller and later Nancy Spero Ad Hoc Committee on Women Artists. The group held strikes, demonstrations, protests, sit-ins, and events primarily at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That same year, Ringgold, along with her fellow artists Jean Toche and Jon Hendricks, was one of the “Judson Trio” charged with desecrating the American flag in an exhibition. convicted and fined $100 People’s Flag Performance, held at Judson Memorial Church in New York. The conviction and fine were later dismissed. In 1971, Ringgold co-founded Where are weis a black female artist collective born out of an exhibition of the same name held by 14 black female artists at the Acts of Art gallery in Greenwich Village.

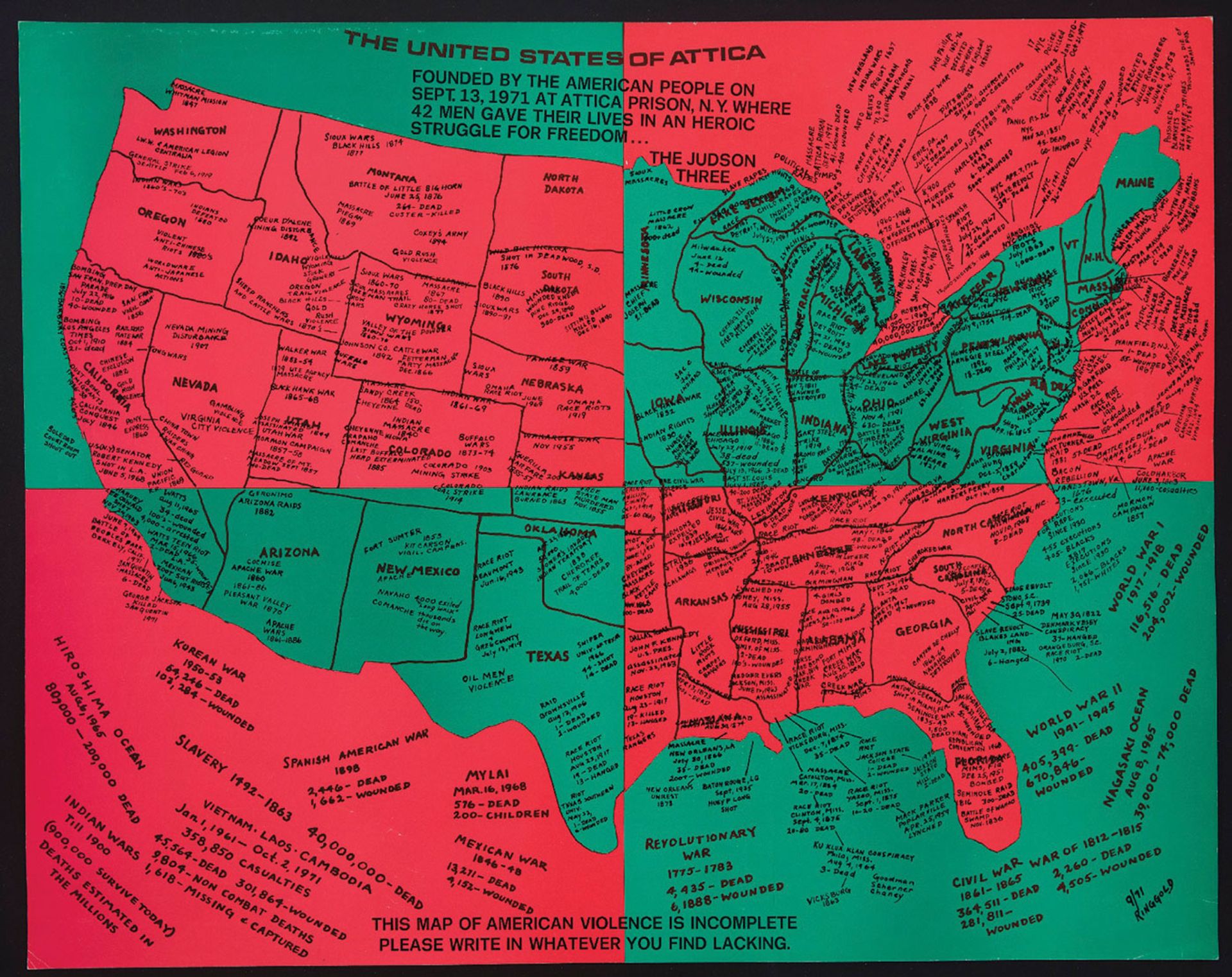

Created by Ringgold United States of Attica (1972) Memorial to those killed in Attica Prison Demonstration © Faith Ringgold/ARS, New York and DACS, London; Courtesy ACA Gallery, New York

Ringgold’s best known works include two public works created for her hometown. In 1971 she produced home for womenis a portable mural at the Rikers Island Women’s Facility. After the building became a men’s prison in 1988, the painting was eventually reinstalled at the Rose M. Singer Center, a new women’s prison, and will be on long-term loan to the Brooklyn Museum. Pair of large mosaics, FLying at Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines (Downtown and Uptown)Work created in 1996 for the 125th subway station in Manhattan, showing Josephine Baker, Malcolm X and Zora Neale Hurston ) and other famous black figures. The title of the work comes from a Lionel Hampton song Ringgold heard as a child. “I wanted to share these memories to give the community and others who pass by a glimpse of all the wonderful people in Harlem,” Ringgold said. “I want them to understand what Harlem created and inspired.”

Textiles and Quilts

Ringgold discovered the Tibetan language Thangka—18th century scroll painting on linen or cotton — during a visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in the early 1970s. “I used some of their forms to create my own Tibetan style,” she told The Art Newspaper In 2019, during the same period, she began creating soft sculptures and masks. She had been inspired by African art since the early 1960s, but it wasn’t until she traveled to Nigeria and Ghana in the 1970s that (according to her own website) she witnessed the “rich mask tradition” that remains ” The one that had the greatest impact on her.”

Ringgold’s quilt work follows Thangka. Her mother taught her to sew paintings from unstretched canvas onto individual cloth backings, and she collaborated with her mother to produce her first, Echoes of Harlem, In 1980, her first story quilt, Who’s afraid of Aunt Jemima? 1983. “My mother was a fashion designer,” Ringgold told The Art Newspaper 2109. They were born slaves and made quilts their entire lives.

“But I don’t make quilts like other people,” she told The Art Newspaper“My images are all painted. I paint on canvas and then sew the painting to other backings. The canvas is just a textile, whether it’s stretched on a stretcher or not.”

Who’s afraid of Aunt Jemima?used to be Created as a direct response to publishers who rejected the typescript of her memoir. In 1998, Ringgold presented two famous series of story quilt paintings in a solo exhibition at the New Museum in New York: french collectiontells the fictional story of a black artist in Paris in the 1920s, and American Collection, in which an artist’s daughter becomes an artist in postwar America. These collections are also on display in her 2022 retrospective at the New Museum.

storyteller

Ringgold is the author of more than a dozen engaging children’s stories, from her critically acclaimed tar bridge (1992), inspired by her own quilt story Woman on the Bridge #1 (of 5): Tar Beach(1988), now in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City. Shown on the quilt is Cassie Louise Lightfoot (we discovered in the 1992 book that she was born one year and 17 days after Ringgold, on October 25, 1931, George, New York City Washington Bridge opened) and her family’s Harlem rooftops, their “Tar Beach.”

Cassie slept at night on Tar Beach, and one summer night she flew across the George Washington Bridge as her little brother watched while her parents and their friends played cards, oblivious. Cassie says in the book that after flying over the bridge, she took possession of it and “could wear it like a giant diamond necklace.” “My woman,” Ringgold said women on bridge series, “Actually Flying; They’re Completely Free. They gain liberation by confronting this giant masculine symbol: the bridge. Titled We Fly Over the Bridge: A Memoir by Faith Ringgold (1995) is an explicit reference to the author’s most famous work of children’s fiction.

Ringgold has used the surname of her late second husband, Burdette Ringgold, since her marriage in 1962 to her first husband, Robert Earl Wallace. ) has two daughters, including writer Michelle Wallace, Black Masculinity and the Myth of Superwoman (1979).

Ringgold remained an educator for nearly half a century after first teaching in New York schools and later becoming professor emeritus of art at the University of California, San Diego. She has been represented worldwide by the historic American Contemporary Art Gallery (ACA Gallery) since 1995, and her other notable solo exhibitions include a 1983 solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Newberg Museum of Art , Purchase New York, 2010; and Serpentine Gallery, London, 2019.

- Faith Willie Jones; born October 8, 1930, New York City; married 1962, Robert Earl Wallace (d. 1961), had two daughters, marriage dissolved 1956 ) married; Burdette Ringgold (died 2020); died April 13, 2024, Englewood, New Jersey.