Doug Caplan, born in Montreal in 1965, first encountered photography as a teenager. His parents handed him a black-and-white Polaroid camera—simple, manual, and chemically scented. It didn’t spark an immediate calling. But it left a trace. The kind that lingers in the back of the mind for years. It wasn’t until the early ’90s, after getting married, that he picked up a camera again. This time, something clicked for good.

Caplan has worked across analog and digital mediums, but the tool isn’t the story. What matters is how he sees. His photographs don’t chase grandeur or drama. They tune into quiet signals, the forgotten parts of city life—places where function overrides form, but meaning still seeps through. Caplan’s work reminds us that the ordinary isn’t empty—it’s just usually overlooked.

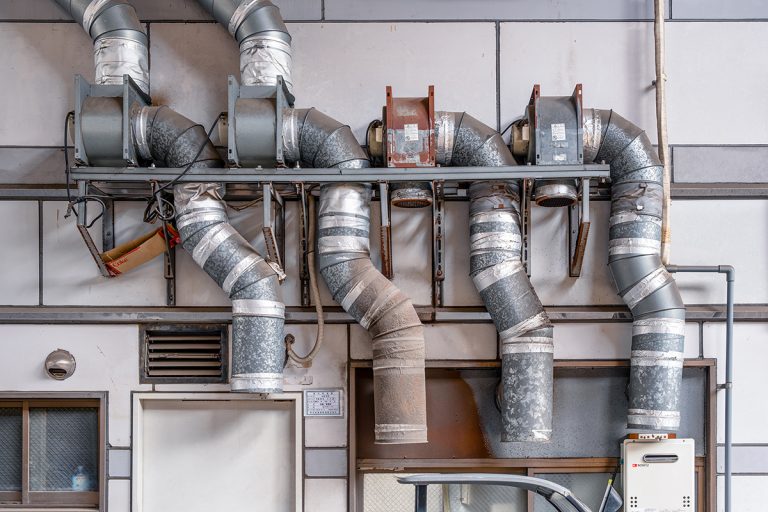

Ductwork Ballet

Ductwork Ballet, taken in Tokyo, shows a mass of industrial piping snaking along the wall of a nondescript building. There are no people, no obvious subject—just the tangled choreography of metal ducts doing their job. And yet, Caplan’s eye turns the scene into something unexpectedly elegant.

Every curve and corner feels like part of a larger rhythm. The pipes don’t follow any design rulebook, but they seem to be in sync anyway. It’s not intentional beauty, but it’s beauty all the same. Caplan doesn’t push a narrative. He simply lets the visual weight of the infrastructure settle into a kind of pattern. What’s meant to be practical begins to resemble movement, almost like a paused dance.

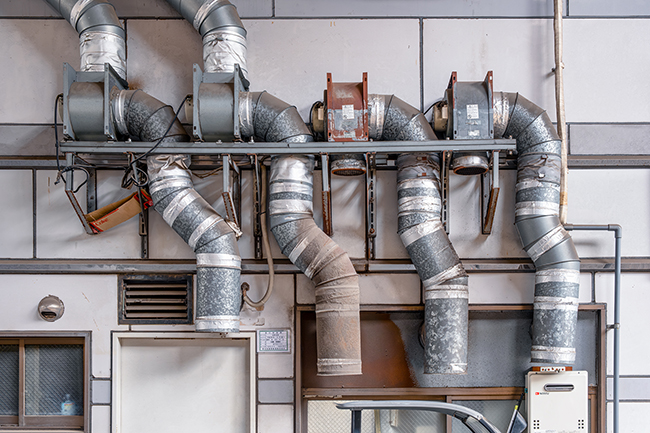

Snakes & Ladders

Also in Tokyo, Snakes & Ladders picks up on a similar idea: how infrastructure can tell a quiet story. The composition includes ladders, wires, vents—everything jumbled, angled, stacked, and crossed. It doesn’t try to clean itself up. That’s the point.

A single yellow window glows in the frame, grounding the chaos in a moment of quiet warmth. There’s life behind it, maybe someone awake at 2 a.m. reading, working, just being. Caplan’s title nods to the board game, but the image feels more meditative than playful. Here, the “game” is the constant dance between design and necessity.

This photo doesn’t glamorize the city’s bones. It reveals them. And asks us to pay attention to what keeps the lights on, the air flowing, the people moving—often without ever being seen.

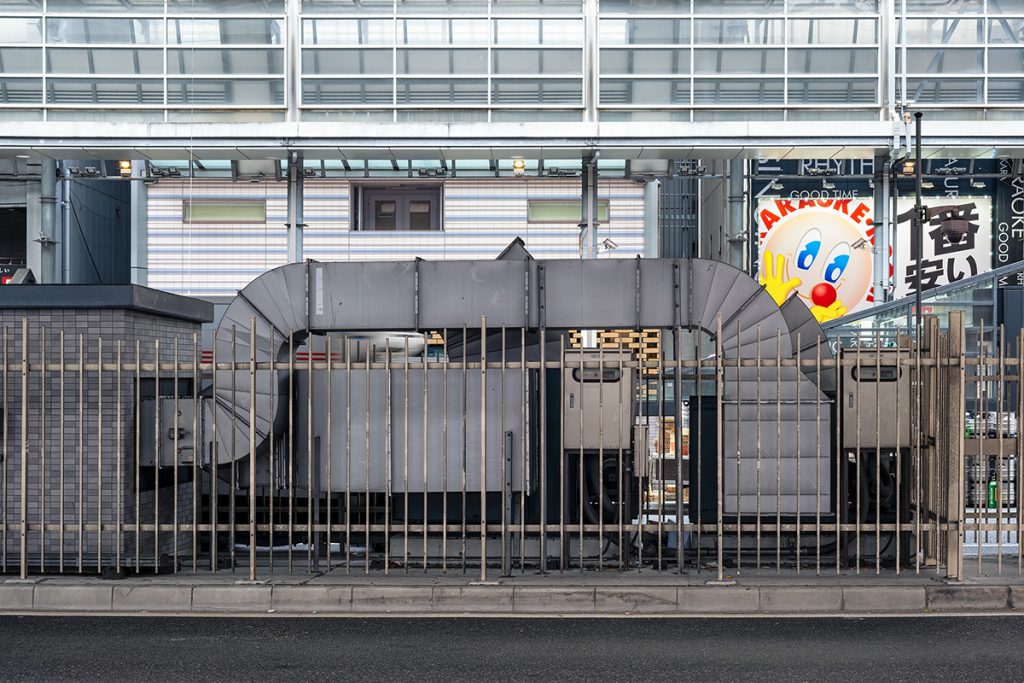

The Absurdity of Existence

In The Absurdity of Existence, shot in Osaka, Caplan leans into visual contradiction. At first, the image feels rigid: straight lines, uniform tones, a setting built for control. Then, right in the middle, a cartoonish, bright face appears—laughing, oversized, and totally at odds with the backdrop.

It shouldn’t work. But somehow, it does.

Rather than treat the interruption as a flaw, Caplan embraces it. The face doesn’t ruin the order—it completes it. It suggests that absurdity isn’t something that sneaks in; it’s embedded in the blueprint. The photo highlights how cities, like people, are built from both structure and randomness. And sometimes, what doesn’t belong actually fits best.

Caplan’s strength lies in seeing what others pass by. Pipes, vents, stickers, ladders—they’re not subjects most photographers chase. But through his lens, they become characters. His photos don’t yell. They wait. And when you give them a second look, they start to tell you something real: that the beauty of a place isn’t always where it’s supposed to be.

Sometimes, it’s crawling up the side of a building. Sometimes, it’s grinning back at you from a wall.