Haeley Kyong doesn’t make art you solve. She makes art you register. There’s a difference. Some work invites analysis before anything else happens. Kyong’s work moves in the opposite direction—it lands in the body first, then the mind catches up. It’s built on a quiet confidence that art can reach us before we find the words for what we’re experiencing, before we file it under meaning, before we decide what it “should” be.

Kyong grew up in South Korea, and later spent formative years in New York, studying at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University and at Columbia University. Those two worlds—early cultural grounding and later academic intensity—show up in the way she works. There’s structure, but also looseness. Control, but also space. You can feel training in the decisions she makes, yet the work never feels like it’s trying to prove anything. It’s more interested in clarity than display.

Her visual language is minimalist, but that doesn’t mean emotionally small. Minimalism often gets mislabeled as cool or distant, as if stripping things down automatically drains feeling out of the room. Kyong’s work argues the opposite: fewer elements can carry more charge, because nothing is competing for attention. The extra is removed, and what remains becomes louder—not in volume, but in presence.

Standing in front of her work, you’re not handed a storyline or a barrage of symbols. You’re offered a tight set of ingredients—shape, color, spacing, rhythm—and the invitation is simple: come closer. Meet it halfway. The experience isn’t one-directional. It’s not the artwork speaking at you. It’s the artwork holding a position and waiting for you to respond.

Kyong tends to build compositions from basic forms and carefully tuned color relationships. What she seems to love is how tiny changes can shift the emotional weather of a piece: a hue leaning warmer by a fraction, an edge softening, a gap opening slightly wider. Those adjustments might look modest on paper, but they change the way the work sits in your nervous system. In that sense, her art behaves like music—limited notes, precise timing, and a mood that changes depending on who’s listening and what they walked in carrying.

That’s where her intent becomes clear. Kyong aims to bypass the overthinking reflex. Her work doesn’t rely on clever tricks or insider references. It relies on recognition—instinctive, immediate. You may not be able to explain why a certain arrangement makes you feel steadier, or uneasy, or suddenly awake, but you feel it anyway. That reaction isn’t separate from the work. It’s part of it.

A piece that holds this approach beautifully is Color Wave. At first glance, it reads as a field of individual tiles, each painted in a different palette—like a mosaic made from many small decisions. The whole is cohesive, but the magnetism is in the differences. Each tile has its own atmosphere. Some read as open and bright. Others feel quieter, held back, almost private. And still, they sit together edge-to-edge, forming one continuous surface.

What Color Wave avoids—skillfully—is turning that idea into a message you can summarize in a sentence. It’s not a slogan about unity. It’s a lived visual experience of it. The tiles keep their individuality without clashing. They don’t flatten into sameness. Contrast becomes the glue. The work makes it easy to think about people and perspectives without preaching: separate lives, separate inner worlds, still sharing one frame.

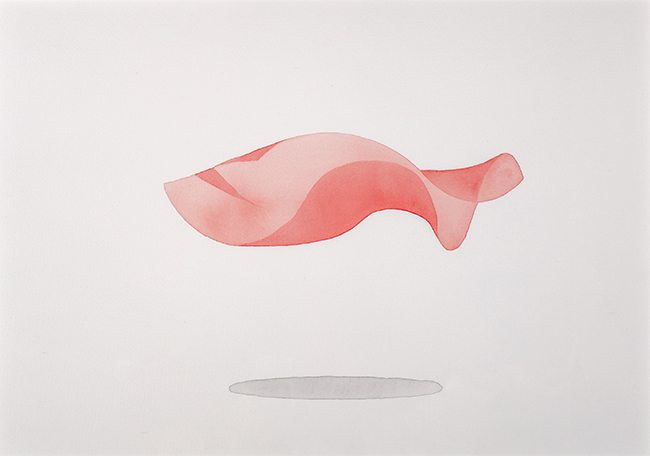

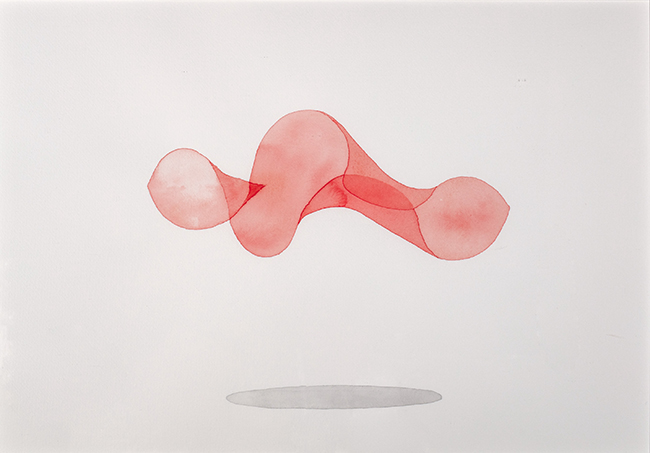

If Color Wave is about many parts forming one field, Kyong’s watercolor series Undulation is about inner motion—the kind that’s hard to name but easy to recognize. The series includes five paintings centered on a simple square that appears to move through space. The form remains straightforward, but the movement is expressive. It dips, lifts, twists, and shifts posture like a body does when it’s deciding something—when it wants to go forward and also wants to retreat.

Kyong has connected Undulation to the flight of a bird, and you can sense that influence in the sense of air and lift. But the work isn’t literally about birds. It’s about what flight stands for: the desire for freedom, and the fact that freedom can arrive tangled with fear. That tension—lift paired with wobble—is what gives the series its emotional pressure. The square becomes a stand-in for the internal fluctuations most people live with: courage, doubt, release, resistance.

Across the five paintings, the square seems to pass through different states, almost like frames in a short sequence. Watercolor does a lot of the emotional work here. The edges soften. Pigment drifts and blooms. The medium refuses rigidity, even when the central form is geometric. It introduces breath—transparency, bleed, a sense of time passing inside the paper. You’re watching a simple shape behave like a feeling, which is exactly why the work stays with you.

What ultimately draws people into Kyong’s practice isn’t elaborate imagery. It’s the steadiness of her choices. She trusts the viewer enough not to over-explain. She sets the conditions for a personal encounter and lets it happen. The work is quiet, but it isn’t passive. It asks for attention, and it rewards it.

Her education plays a subtle role in that restraint. Training can tempt artists into overbuilding—adding more to show capability, filling every corner to prove range. Kyong goes the other direction. She refines instead of decorating. The work feels resolved without feeling overworked. There’s room for the viewer to think, and more importantly, room for the viewer to feel without being instructed.

At the center of Kyong’s practice is introspection—not as a trendy term, but as a real moment: noticing your own response as it’s happening. Her pieces can function like a pause. They slow the internal noise just enough for something honest to surface.

Maybe that’s the quiet argument her work makes: we don’t always need more information. Sometimes we need less—less clutter, less speed, less performance—so what’s already inside us can become clear.

Haeley Kyong creates work that is pared down and deeply affecting. With a small set of tools—shape, color, rhythm—she opens a wide emotional field. The work doesn’t shout for attention. It holds its ground. And in that steady focus, it offers something rare: a clean space where a person can reflect, reset, and recognize themselves.