Sylvia Nagy’s path as an artist blends structure and sensitivity. Trained in industrial ceramics, she began her formal studies at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest, where she received her MFA in Silicet Industrial Technology and Art. Later, in New York, she deepened her connection to both making and teaching while at Parsons School of Design. There, she wasn’t just passing through—she taught and even built a course around mold-making in plaster. Her approach combines the control of engineering with the freedom of improvisation. And it’s taken her far: from Hungary to Japan, China, Germany, and the United States. Each place has added something to her way of thinking. Now a member of the International Academy of Ceramics in Geneva, her work appears in museum collections across Europe and Asia. When she’s not working with clay, she draws from her love of movement, style, photography, and contemporary design.

Nagy doesn’t treat clay as just another medium. For her, it’s a tool for tuning in—something closer to language than material. She talks about the soul’s link to the earth and how clay becomes a mirror for that connection. Her creative process isn’t linear or tightly planned. Instead, she follows a kind of inner signal—what she calls intuition, which “doesn’t speak English.” It speaks through mood, through timing, through energy. Her sculptures don’t begin with a fixed idea. They take shape as they go.

Her art isn’t reactive, but it’s not disconnected either. She pays attention to what’s happening around her—political unrest, environmental collapse, sudden shifts in human behavior. She notices what others might overlook: the warnings before the fall. Her ceramics are a way of turning those observations into something tactile. Something that doesn’t just get looked at, but felt.

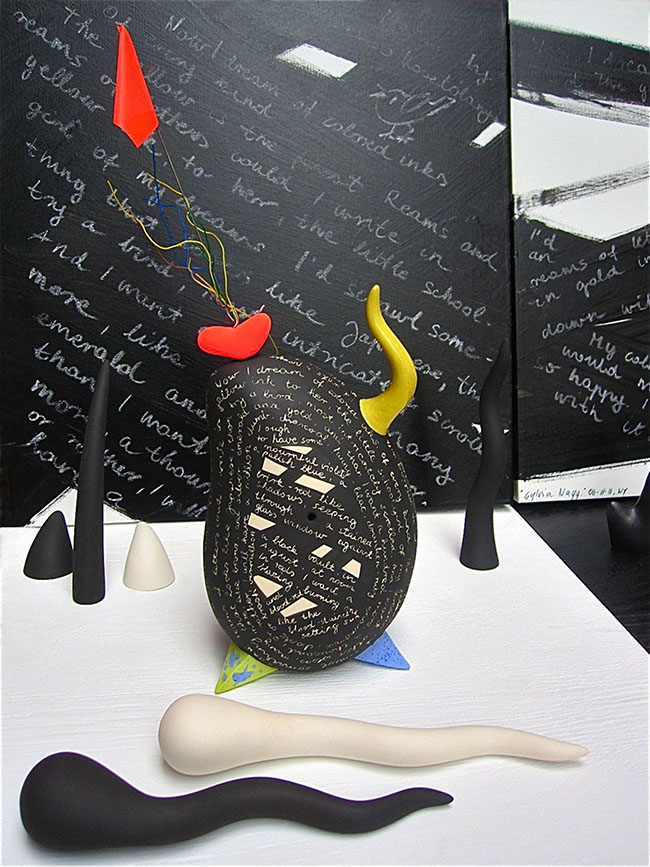

There’s a quiet energy running through her work. It isn’t about symmetry or surface polish. It’s about pulse, presence, and sensation. Some forms might seem ancient, some look abstract, but all of them carry a kind of frequency—like a low hum or a breath. She brings in ideas from physics and science, drawing on things like quantum theory, energy fields, and the unseen forces that shape us. She doesn’t try to explain these ideas directly. Instead, they find their way into her textures, her rhythms, her forms.

Her curiosity spills over into education and therapy. She’s led ceramic workshops for children in foster care, people with disabilities, the elderly, and college students. She sees working with clay as a form of healing—not in a clinical sense, but as a way to help people reconnect with their bodies, their emotions, their own story. Clay doesn’t rush. It needs time, contact, repetition. That process alone can be grounding.

Across many cultures, ceramics have held sacred and personal meaning. They weren’t just dishes or tools; they were a part of rituals, belief systems, ways of remembering. Nagy honors that history while bringing it forward. Her pieces don’t chase perfection. They carry layers—cracks, grooves, weight. Sometimes they look as if they’ve come from the earth itself, dug up rather than built.

Her art doesn’t demand attention. It lingers instead. You don’t need to “get it” right away. She invites you to pause, sit with it, and see what stirs. For Nagy, that’s what matters—making work that helps people slow down, tune in, and feel their way through.

Sylvia Nagy uses clay as a conversation, not a statement. She’s not trying to impress or provoke. She’s trying to stay connected—to the physical world, to the flow of time, and to the subtle things that often go unnoticed. Her work reminds us to stop and listen. Even if we don’t speak the language, something always comes through.